The day after the Titanic sank, newspapers around the world reported that all the passengers aboard had been saved. The World declared, “Titanic Sinking; No Lives Lost.” The Evening Sun proclaimed, “All Saved from Titanic After Collison.” The Vancouver Daily Province reported, “The Titanic Sinking, But Probably No Lives Lost.” Only The New York Times hit close to the truth with a lengthy headline which read: “Titanic Sinks Four Hours After Hitting Iceberg; 866 Rescued By Carpathia, Probably 1,250 Perish; Ismay Safe, Mrs. Astor Maybe, Noted Names Missing.”

In reality, 1,514 people lost their lives in the early morning hours of 15 April 1912.

How could so many newspapers get it so wrong? It turns out that during the course of wireless chatter someone asked: “Are the Titanic passengers safe?” An answer came: “The ship is being towed to Halifax and everyone is ok.” The only problem was that the second transmission didn’t refer to the Titanic. When reporters got wind of the story, many of them called folks along the Canadian coast to corroborate details. Misinformation spread like wildfire.

Christopher Sullivan, an editor at Associated Press in New York who researched the origins of this catastrophic error, said: “At the very beginning, when the story is just developing, there’s so much confusion and everyone is doing everything they possibly can to grab any piece of information.” American newspapers had a slight advantage over their British counterparts given the five-hour time difference between the United States and Britain, which bought them time to verify facts. Even so, inaccurate reporting persisted on both sides of the Atlantic.

This got me thinking about some of the lesser-known stories involving the world’s most famous maritime disaster. Many people are well-versed in the history of the Titanic. But one story that rarely gets any attention is what happened to the bodies of those who died that fateful morning. Some sank to the bottom of the sea, but not all. Many victims who were wearing life jackets merely bobbed upon the surface of the water: a grisly reminder of the extraordinary loss of life that arose from the accident.

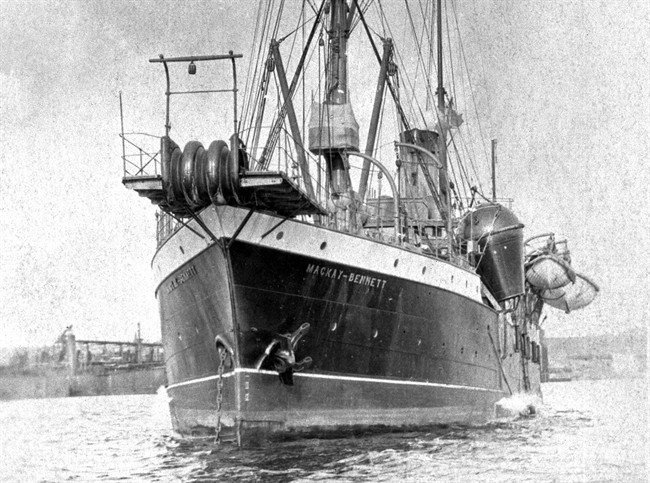

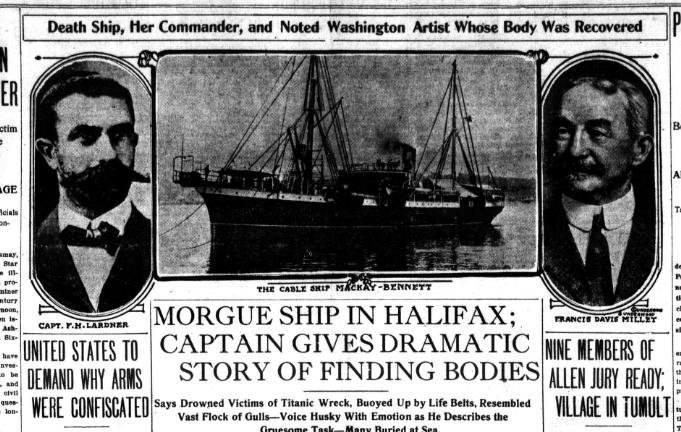

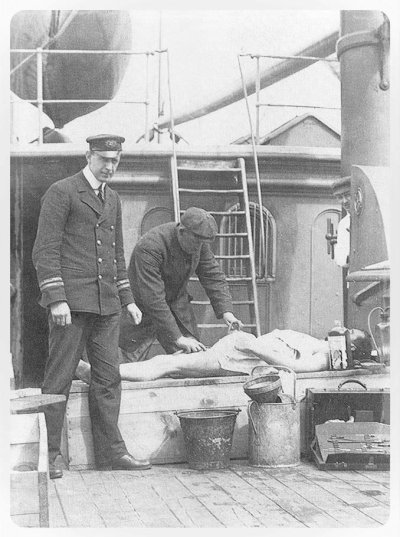

This is a photo [left] of an unidentified victim of the Titanic being embalmed on the deck of the Mackay Bennett, which was one of four ships chartered by the White Star Line to collect bodies shortly after the disaster. The grim task took several days, with one observer describing how he “grew sick of the sight” of dead bodies. Dr. Thomas Armstrong, the Ship’s Surgeon on the Mackay Bennett, recalled: “With the exception of about 10 bodies that had received serious injuries, their looks were calm and peaceful.” In the end, the Mackay Bennett and its crew were able to recover over 300 bodies, including that of business tycoon John Jacob Astor, who was identified by the jewelry he wore and a few cards found in a card case in his pocket.

It took two days to ready the ship, and four days to reach the site of the disaster. When it finally reached its destination, the Mackay Bennett was carrying with it 100 coffins, 100 tons of ice, and 12 tons of iron bars which were used to bury badly decomposed bodies at sea. Passenger bodies that were in “satisfactory condition” were embalmed.

Unfortunately, the crew of the Mackay Bennett was unprepared for the sheer number of bodies that they would encounter. Later, the captain explained why so many of those recovered ultimately had to be buried at sea: “When we left Halifax we took on board all of the embalming fluid in the city. That was only enough to care for seventy bodies. It wasn’t expected that we would find bodies in such great quantities.”

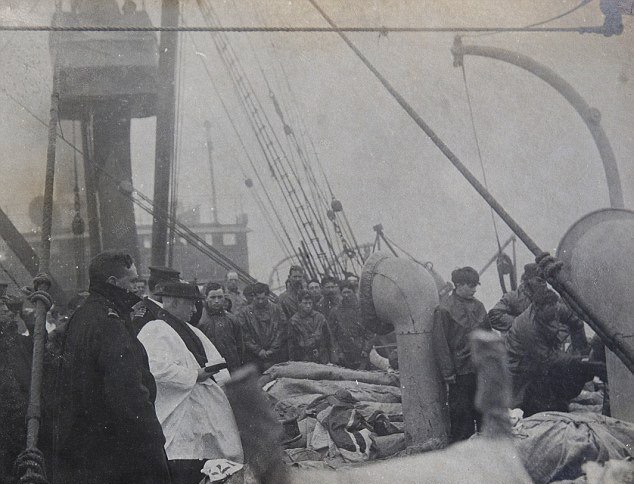

When possible, those identified as first-class passengers were placed in coffins, while second and third-class passengers were wrapped in canvas. Crew members were simply placed into the ice-filled hold or buried at sea. The Captain said: “The undertaker didn’t think these bodies would keep more than three days at sea, and as we expected to be out more than two weeks we had to bury them. They received the full services for the dead before they were put over.” Even in death, people were sorted according to their class.

On 30 April 1912, The Washington Times reported: “As the Mackay-Bennett slowly steamed up the three and one-half miles of the harbor, the bells in the church towers tolled solemnly at minute intervals, and thousands of the city’s inhabitants hurried to points of vantage along the waterfront to catch the first glimpse of the ship with her cargo of dead.” Relatives of the victims were kept away for several days while the bodies were prepared by undertakers, one of whom had the misfortune of discovering his own uncle amongst the drowned corpses pulled from the sea.

About half of those recovered were buried across three cemeteries in Halifax; forty-two bodies went unidentified. Their tombstones contain a simple number and the date of the disaster. Only twenty-three percent of the total number of people who died during the sinking were ever found.

If you enjoy my content, please consider supporting it here.