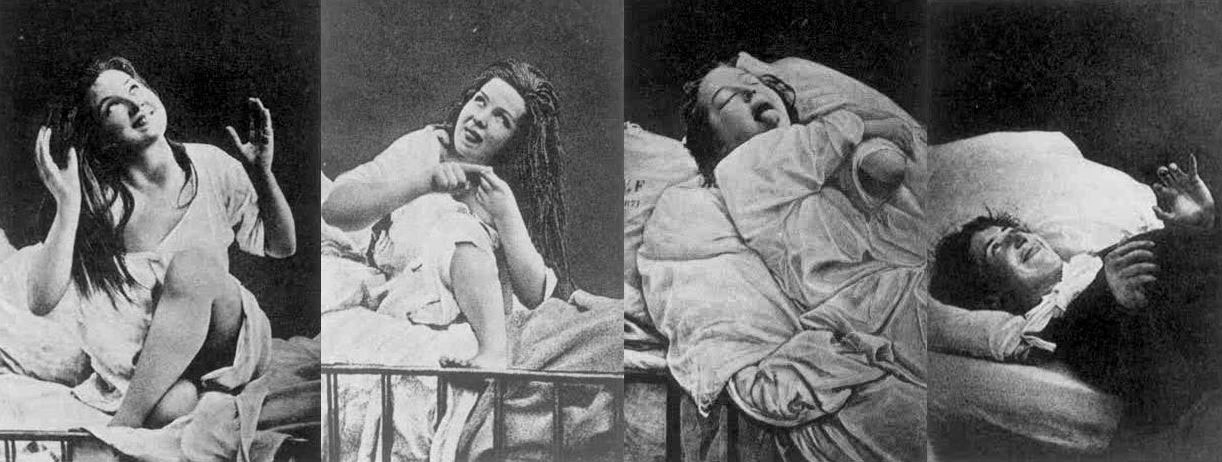

The word “hysteria” conjures up an array of images, none of which probably include a nomadic uterus wandering aimlessly around the female body. Yet that is precisely what medical practitioners in the past believed was the cause behind this mysterious disorder. The very word “hysteria” comes from the Greek word hystera, meaning “womb,” and arises from medical misunderstandings of basic female anatomy.

Today, hysteria is regarded as a physical expression of a mental conflict and can affect anyone regardless of age or gender. [1] Centuries ago, however, it was attributed only to women, and believed to be physiological (not psychological) in nature.

For instance, Plato believed that the womb—especially one which was barren—could become vexed and begin wandering throughout the body, blocking respiratory channels causing bizarre behavior. [2] This belief was ubiquitous in ancient Greece. The physician Aretaeus of Cappadocia went so far as to consider the womb “an animal within an animal,” an organ that “moved of itself hither and thither in the flanks.” [3] The uterus could move upwards, downwards, left or right. It could even collide with the liver or spleen. Depending on its direction, a wandering womb could cause all kinds of hell. One that traveled upwards might cause sluggishness, lack of strength, and vertigo in a patient; while a womb that moved downwards could cause a person to feel as if she were choking. So worrisome was the prospect of a wandering womb during this period, that some women wore amulets to protect themselves against it. [4]

For instance, Plato believed that the womb—especially one which was barren—could become vexed and begin wandering throughout the body, blocking respiratory channels causing bizarre behavior. [2] This belief was ubiquitous in ancient Greece. The physician Aretaeus of Cappadocia went so far as to consider the womb “an animal within an animal,” an organ that “moved of itself hither and thither in the flanks.” [3] The uterus could move upwards, downwards, left or right. It could even collide with the liver or spleen. Depending on its direction, a wandering womb could cause all kinds of hell. One that traveled upwards might cause sluggishness, lack of strength, and vertigo in a patient; while a womb that moved downwards could cause a person to feel as if she were choking. So worrisome was the prospect of a wandering womb during this period, that some women wore amulets to protect themselves against it. [4]

The womb continued to hold a mystical place in medical text for centuries, and was often used to explain away an array of female complaints. The 17th-century physician William Harvey, famed for his theories on the circulation of the blood around the heart, perpetuated the belief that women were slaves to their own biology. He described the uterus as “insatiable, ferocious, animal-like,” and drew parallels between “bitches in heat and hysterical women.” [5] When a woman named Mary Glover accused her neighbor Elizabeth Jackson of cursing her in 1602, the physician Edward Jorden argued that the erratic behavior that drove Mary to make such an accusation was actually caused by noxious vapors in her womb, which he believed were slowly suffocating her. (The courts disagreed and Elizabeth Jackson was executed for witchcraft shortly thereafter.)

So what could be done for hysteria in the past?

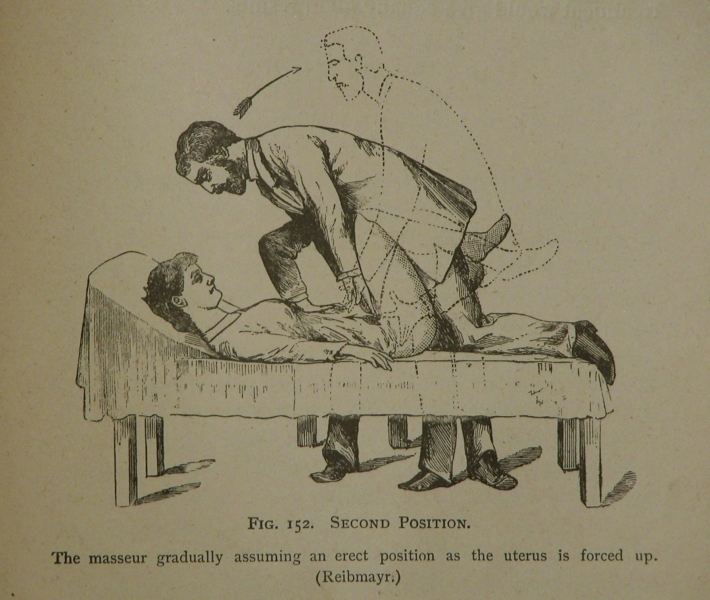

Physicians prescribed all kinds of treatments for a wayward womb. These included sweet-smelling vaginal suppositories and fumigations used to tempt the uterus back to its rightful place. The Greek physician Atreaus wrote that the womb “delights…in fragrant smells and advances towards them; and it has an aversion to foetid smells, and flees from them.” Women were also advised to ingest disgusting substances—sometimes containing repulsive ingredients such as human or animal excrement—in order to coax the womb away from the lungs and heart. In some cases, physical force was used to correct the position of a wandering womb (see image, right). For the single woman suffering from hysteria, the cure was simple: marriage, followed by children. Lots and lots of children.

Physicians prescribed all kinds of treatments for a wayward womb. These included sweet-smelling vaginal suppositories and fumigations used to tempt the uterus back to its rightful place. The Greek physician Atreaus wrote that the womb “delights…in fragrant smells and advances towards them; and it has an aversion to foetid smells, and flees from them.” Women were also advised to ingest disgusting substances—sometimes containing repulsive ingredients such as human or animal excrement—in order to coax the womb away from the lungs and heart. In some cases, physical force was used to correct the position of a wandering womb (see image, right). For the single woman suffering from hysteria, the cure was simple: marriage, followed by children. Lots and lots of children.

Today, wombs are no longer thought to wander; however, medicine still tends to pathologize the vagaries of the female reproductive system. [6] Over the course of several thousand years, the womb has become less of a way to explain physician ailments, and more of a way to explain psychological disfunction—often being cited as the reason behind irrationality and mood swings in women. Has the ever-elusive hysteria brought on by roving uteri simply been replaced by the equally intangible yet mysterious PMS? I’ll let you decide.

You can now pre-order my book THE BUTCHERING ART by clicking here. THE BUTCHERING ART follows the story of Joseph Lister as he attempts to revolutionize the brutal world of Victorian surgery through antisepsis. Pre-orders are incredibly helpful to new authors. Info on how to order foreign editions coming soon. Your support is greatly appreciated.

1. Mark J Adair, “Plato’s View of the ‘Wandering Uterus,’” The Classical Journal 91:2 (1996), p. 153.

2. G. S. Rousseau, “‘A Strange Pathology:’ Hysteria in the Early Modern World, 1500-1800” in Hysteria Beyond Freud (1993), p.104. Originally qtd in Heather Meek, “Of Wandering Wombs and Wrongs of Women: Evolving Concepts of Hysteria in the Age of Reason,” English Studies in Canada 35:2-3 (June/September 2009), p.109.

3. Quoted in Matt Simon, “Fantastically Wrong: The Theory of the Wandering Wombs that Drove Women to Madness,” Wired (7 May 2014).

4. Robert K. Ritner, “A Uterine Amulet in the Oriental Institute Collection,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 45:3 (Jul. 1984), pp.209-221. For more on the fascinating subject of magical amulets, see Tom Blaen, Medical Jewels, Magical Gems: Precious Stones in Early Modern Britain (2012).

5. Rousseau, “A Strange Pathology,” p. 132.

6. Mary Lefkowitz, “Medical Notes: The Wandering Womb,” The New Yorker (26 February 1996).