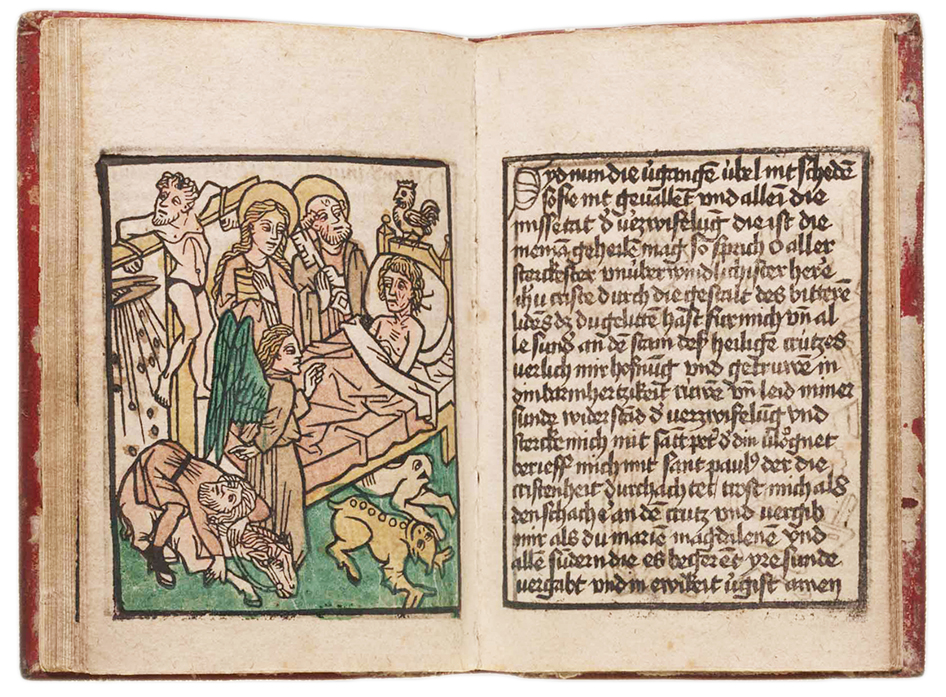

When the Black Death swept through Europe in the 14th century, it claimed the lives of over 75 million people, many of who were clergymen whose job it was to help usher the dying into the next world. In response to the shortage of priests, the Ars Moriendi (Art of Dying) first emerged in 1415. This was a manual that provided practical guidance to the dying and those who attended them in their final moments. These included prayers and prescribed rites to be performed at the deathbed, as well as illustrations and descriptions of the temptations one must overcome in order to achieve a “good death.”

From the medieval period onwards, the dying were expected to follow a set of “rules” when facing the final moments of their lives, which included repentance of sins, forgiving enemies, and accepting one’s fate stoically without complaint. It was each person’s duty to die a righteous death.

In earlier periods, many people believed that pain was a necessary component of a good death. Indeed, the word patient comes from the Latin word patiens, meaning “long-suffering” or “one who suffers.” Evangelical Christians, in particular, feared losing lucidity as death approached, as this would prohibit the person from begging forgiveness for past sins and putting his or her worldly affairs in order before departing this life. Death was a public event, with those closest to the dying in attendance. Friends and relatives were not merely passive observers. They often assisted the dying person in his or her final hours, offering up prayers as the moment drew closer. The deathbed presented the dying with the final opportunity for eternal salvation.

In earlier periods, many people believed that pain was a necessary component of a good death. Indeed, the word patient comes from the Latin word patiens, meaning “long-suffering” or “one who suffers.” Evangelical Christians, in particular, feared losing lucidity as death approached, as this would prohibit the person from begging forgiveness for past sins and putting his or her worldly affairs in order before departing this life. Death was a public event, with those closest to the dying in attendance. Friends and relatives were not merely passive observers. They often assisted the dying person in his or her final hours, offering up prayers as the moment drew closer. The deathbed presented the dying with the final opportunity for eternal salvation.

For this reason, the physician rarely appeared at the bedside of a dying person because pain management wasn’t required. Moreover, the general consensus was that it was inappropriate for a person to profit from another’s death. Caricatures depicting the greedy physician running off with bags of money after his patient had succumbed to his fate were not uncommon in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Over time, however, religious sentiments faded, and physicians began to appear more regularly in the homes of the dying. Part of this was driven by the fact that doctors became more effective at pain management. At the start of the 19th century, they typically administered laudanum drops orally to patients. This process was imprecise, and sometimes not effective at all. All this changed in 1853 when Charles Pravaz and Alexander Wood developed a medical hypodermic syringe with a needle fine enough to pierce the skin (see example below from c.1880). From that point onwards, physicians began administering morphine intravenously, which was far more effective (though also more dangerous). As new techniques emerged, people’s attitudes towards pain management in treating the dying began to change. Soon, a painless death was not only seen to be acceptable, but also vital to achieving a “good death.”

The doctor’s place at the bedside of the dying became increasingly more commonplace. Whereas the deathbed was formerly governed by religious tradition, it now became the purview of the medical community. The emphasis for the doctor had shifted from cure to care by the end of the 19th century, thus making his place in the “death chamber” more acceptable. Now, the good physician was one who stood by his patient, even when nothing could be done to save his or her life. As the legal scholar Shai Lavi succinctly put it: “The ethics of the deathbed shifted from religion to medicine, and dying further emerged as a matter of regulating life: life was now understood in its biological, rather than biographical, sense.”

The medicalization of death had arrived, one which for better or worse continues to shape how we die today.

If you enjoy my blog, please consider supporting my content by clicking HERE.

Suggested Reading:

- Shai Lavi, “Euthanasia and the Changing Ethics of the Deathbed: A Study in Historical Jurisprudence,” Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 4.2 (2003): pp. 729 – 761.