I remember rummaging through an old trunk in my grandmother’s house when I was a child and coming across what seemed to me at the time a very unusual photograph. It was a monochromatic image of a beautiful, young woman lying in a white casket (not dissimilar to the photo on the left).

I remember rummaging through an old trunk in my grandmother’s house when I was a child and coming across what seemed to me at the time a very unusual photograph. It was a monochromatic image of a beautiful, young woman lying in a white casket (not dissimilar to the photo on the left).

Curious, I plucked the photo from the trunk and went to find my grandma, who was parked at the kitchen table sorting through the piles of mail that inevitably found its way into her house everyday. She told me that the woman in the casket was a distant relative of mine named Lena, who had died tragically at the age of 17. “You know, people used to take photos of the dead back then,” she said, taking the picture from me and studying it closely as if she had never seen it before. “Imagine that,” she remarked before placing the photo on the kitchen table and turning her attention back to the endless heaps of mail sitting on the table.

To a child, the image was haunting, and I never quite forgot it. It wasn’t till later in life, however, that I understood the historical significance behind the photo.

My grandmother was right (something she relishes hearing even to this day). Postmortem photos began to emerge shortly after commercial photography itself became available in 1839, and carried on being popular into the early 20th century. This was a time when people in Western Europe and North America had an intimate relationship with the dead, so it was inevitable that the recently deceased would feature prominently in Victorian family albums. The fact that my grandma only has one postmortem photo in her possession is now more unusual to me than the image itself.

My grandmother was right (something she relishes hearing even to this day). Postmortem photos began to emerge shortly after commercial photography itself became available in 1839, and carried on being popular into the early 20th century. This was a time when people in Western Europe and North America had an intimate relationship with the dead, so it was inevitable that the recently deceased would feature prominently in Victorian family albums. The fact that my grandma only has one postmortem photo in her possession is now more unusual to me than the image itself.

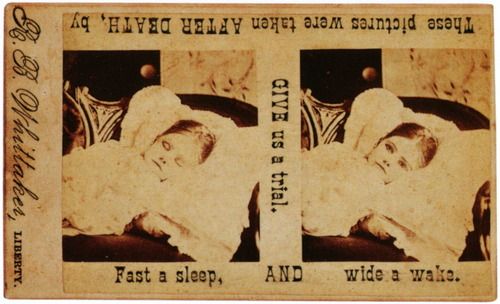

Postmortem photos from the Victorian period varied considerably in presentation. The dead were not always photographed in their caskets, as you might expect. Often, they were propped up in chairs, occasionally alongside the living. This was especially common when the deceased was a child, as in this example above.

Sometimes, the dead’s cheeks were coloured to mask the telltale signs of decomposition, or the eyes drawn over to look as if they were open. R. B. Whittaker in New York described the latter services as “Fast Asleep and Wide Awake” in an advertisement card from 1860.

Other times, the corpse did not appear in the photo at all. Rather, it showed the gravesite with mourners standing around a tombstone. Yet no matter how different each photo was from another, death was always at the heart of these images.

By far one of the most unusual postmortem photos I’ve come across is that of Thomas & Mary Souder (below), taken at the time of their deaths in July, 1921. The couple died within 48 hours of each other from “the flux,” known today as dysentery—an intestinal inflammation that causes severe diarrhea that leads to rapid loss of fluids, dehydration and eventually death.

There are two forms of dysentery. One is caused by a bacterium, the other, an amoeba. The former is the most common in Western Europe and the United States; and is typically spread through contaminated food and water. Many people succumbed to the flux in the 19th and early 20th centuries, especially during wartime when access to clean water was severely restricted.

Thomas and Mary were in their late 70s and early 80s when they contracted the disease, and so their untimely demise is not shocking, especially when we consider this occurred before the discovery of penicillin (1928). What is surprising, though, is the double casket in which they were buried. For me, it raises many questions: was the casket commissioned while the two were dying or after both had passed away? And if the latter, how long had the Souders been dead before this photo was taken?

The Fort Worth Star Telegram in Hurst, Texas reported the deaths of the Souders on 16 July 1921:

Even death failed to separate Jefferson Souder…and Mrs. Mary E. Souder…his wife for more than half a century. Side by side, they will be laid to rest in the same casket in the little cemetery at Hurst Sunday afternoon after the span of more than an average lifetime, during with they were never separated. Only a few days intervened between their deaths. Mrs. Souder passed away at the old home near Hurst Wednesday. Her husband’s death followed Friday afternoon.

The simple stone that marks their graves in Arwine Cemetery today gives no hint at the extraordinary casket that lies beneath the ground.

The simple stone that marks their graves in Arwine Cemetery today gives no hint at the extraordinary casket that lies beneath the ground.

Sadly, this is not the only time two people have been buried together. In 2008, Ben and Arron Peak, two brothers who died tragically in a drunk driving accident, were buried in a double casket painted with the colours and logo of Manchester United, the boys’ favourite football team. Wilfred and Ann Fallows—husband and wife—were also buried this way after they died in a head-on collision in 2012. Most recently, Kelsey and Kendall Adams—two young children who were brutally murdered in New Orleans last year—were laid side-by-side and buried together.

So, as intrigued as I was by the Souders’ postmortem photo, I, for one, am glad that the double casket does not appear more frequently in my research. For when it does, it almost always involves a tragic tale filled with sorrow and unthinkable grief.