If you visit the Gordon Museum at Guy’s Hospital in London, you’ll see a small bladder stone—no bigger than 3 centimetres across. Besides the fact that it has been sliced open to reveal concentric circles within, it is entirely unremarkable in appearance. Yet, this tiny stone was the source of enormous pain for 53-year-old Stephen Pollard, who agreed to undergo surgery to remove it in 1828.

People frequently suffered from bladder stones in earlier periods due to poor diet, which often consisted of lots of meat and alcohol, and very few vegetables. The oldest bladder stone on record was discovered in Egyptian grave from 4,800 B.C. The problem was so common that itinerant healers traveled from village to village offering a vast array of services and potions that promised to cure those suffering from the condition. Depending on the size of these stones, they could block the flow of urine into the bladder from the kidneys; or, they could prevent the flow of urine out of the bladder through the urethra. Either situation was potentially lethal. In the first instance, the kidney is slowly destroyed by pressure from the urine; in the second instance, the bladder swells and eventually bursts, leading to infection and finally death.

Like today, bladder stones were unimaginably painful for those who suffered from them in the past. The stones themselves were often enormous. Some measured as large as a tennis ball. The afflicted often acted in desperation, going to great lengths to rid themselves of the agony. In the early 18th century, one man reportedly drove a nail through his penis and then used a blacksmith’s hammer to break the stone apart until the pieces were small enough to pass through his urethra. It’s not a surprise, then, that many sufferers chose to submit to the surgeon’s knife despite a very real risk of dying during or immediately after the procedure from shock or infection. Although the operation itself lasted only a matter of minutes, lithotomic procedures were incredibly painful and dangerous—not to mention humiliating.

Like today, bladder stones were unimaginably painful for those who suffered from them in the past. The stones themselves were often enormous. Some measured as large as a tennis ball. The afflicted often acted in desperation, going to great lengths to rid themselves of the agony. In the early 18th century, one man reportedly drove a nail through his penis and then used a blacksmith’s hammer to break the stone apart until the pieces were small enough to pass through his urethra. It’s not a surprise, then, that many sufferers chose to submit to the surgeon’s knife despite a very real risk of dying during or immediately after the procedure from shock or infection. Although the operation itself lasted only a matter of minutes, lithotomic procedures were incredibly painful and dangerous—not to mention humiliating.

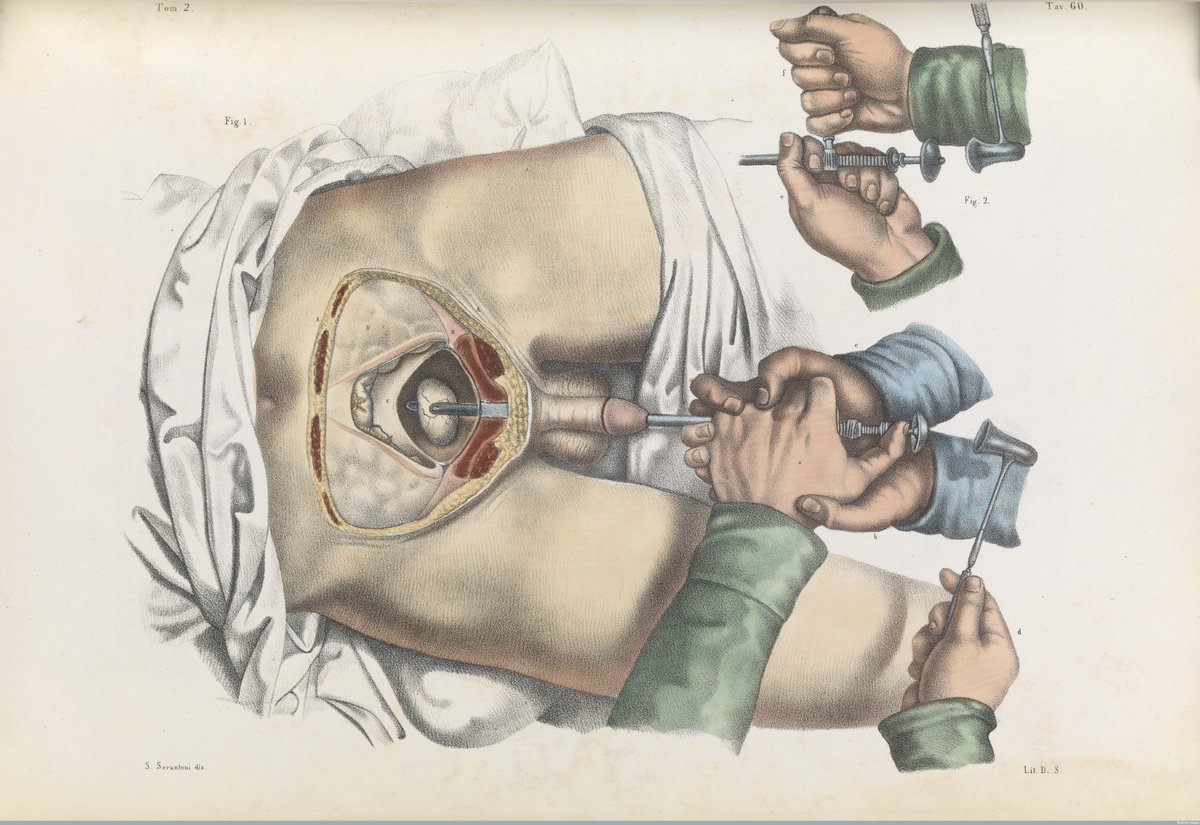

The patient—naked from the waist down—was bound in such a way as to ensure an unobstructed view of his genitals and anus [see illustration below]. Afterwards, the surgeon passed a curved, metal tube up the patient’s penis and into the bladder. He then slid a finger into the man’s rectum, feeling for the stone. Once he had located it, his assistant removed the metal tube and replaced it with a wooden staff. This staff acted as a guide so that the surgeon did not fatally rupture the patient’s rectum or intestines as he began cutting deeper into the bladder. Once the staff was in place, the surgeon cut diagonally through the fibrous muscle of the scrotum until he reached the wooden staff. Next, he used a probe to widen the hole, ripping open the prostate gland in the process. At this point, the wooden staff was removed and the surgeon used forceps to extract the stone from the bladder. [1]

Unfortunately for Stephen Pollard, what should have lasted 5 minutes ended up lasting 55 minutes under the gaze of 200 spectators at Guy’s Hospital in London. The surgeon Bransby Cooper fumbled and panicked, cursing the patient loudly for having “a very deep perineum,” while the patient, in turn, cried: “Oh! let it go; —pray, let it keep in!’” The surgeon reportedly used every tool at his disposal before he finally reached into the gaping wound with his bare fingers. During this time, several of the spectators walked out of the operating theater, unable to bear witness to the patient’s agony any longer. Eventually, Cooper located the stone with a pair of forceps. He held it up for his audience, who clapped unenthusiastically at the sight of the stone.

Sadly, Pollard survived the surgery only to die the next day. His autopsy revealed that it was indeed the skill of his surgeon, and not his alleged “abnormal anatomy,” which was the cause of his death.

But the story didn’t end there. Word quickly got out about the botched operation. When Thomas Wakley [left]—the editor of The Lancet—heard of this medical disaster, he accused Cooper of incompetence and implied that the surgeon had only been appointed to Guy’s Hospital because he was nephew to one of the senior surgeons on staff. Wakley used the trial to attack what he believed to be corruption within the hospitals due to rampant nepotism. Outraged by the allegation, Cooper sued Wakley for libel and sought £2000 in damages. The jury reluctantly sided with the surgeon, but only awarded him £100. Wakley had raised more than that in a defence fund campaign and gave the remaining money over to Pollard’s widow after the trial. [2]

But the story didn’t end there. Word quickly got out about the botched operation. When Thomas Wakley [left]—the editor of The Lancet—heard of this medical disaster, he accused Cooper of incompetence and implied that the surgeon had only been appointed to Guy’s Hospital because he was nephew to one of the senior surgeons on staff. Wakley used the trial to attack what he believed to be corruption within the hospitals due to rampant nepotism. Outraged by the allegation, Cooper sued Wakley for libel and sought £2000 in damages. The jury reluctantly sided with the surgeon, but only awarded him £100. Wakley had raised more than that in a defence fund campaign and gave the remaining money over to Pollard’s widow after the trial. [2]

Bransby Cooper’s reputation, like his patient, never did recover.

If you’re interested in the history of pre-anesthetic and pre-antiseptic surgery, you can pre-order my book The Butchering Art in the US (click here) and in the UK (click here). Information of foreign editions to come!

1. Druin Burch, Digging up the Dead: Uncovering the Life and Times of an Extraordinary Surgeon (2007), p. 26. I am greatly indebted to his work for bringing this story to my attention.

2. Thomas Wakley, A Report of the Trial of Cooper v. Wakley (1829), pp. 4-5.