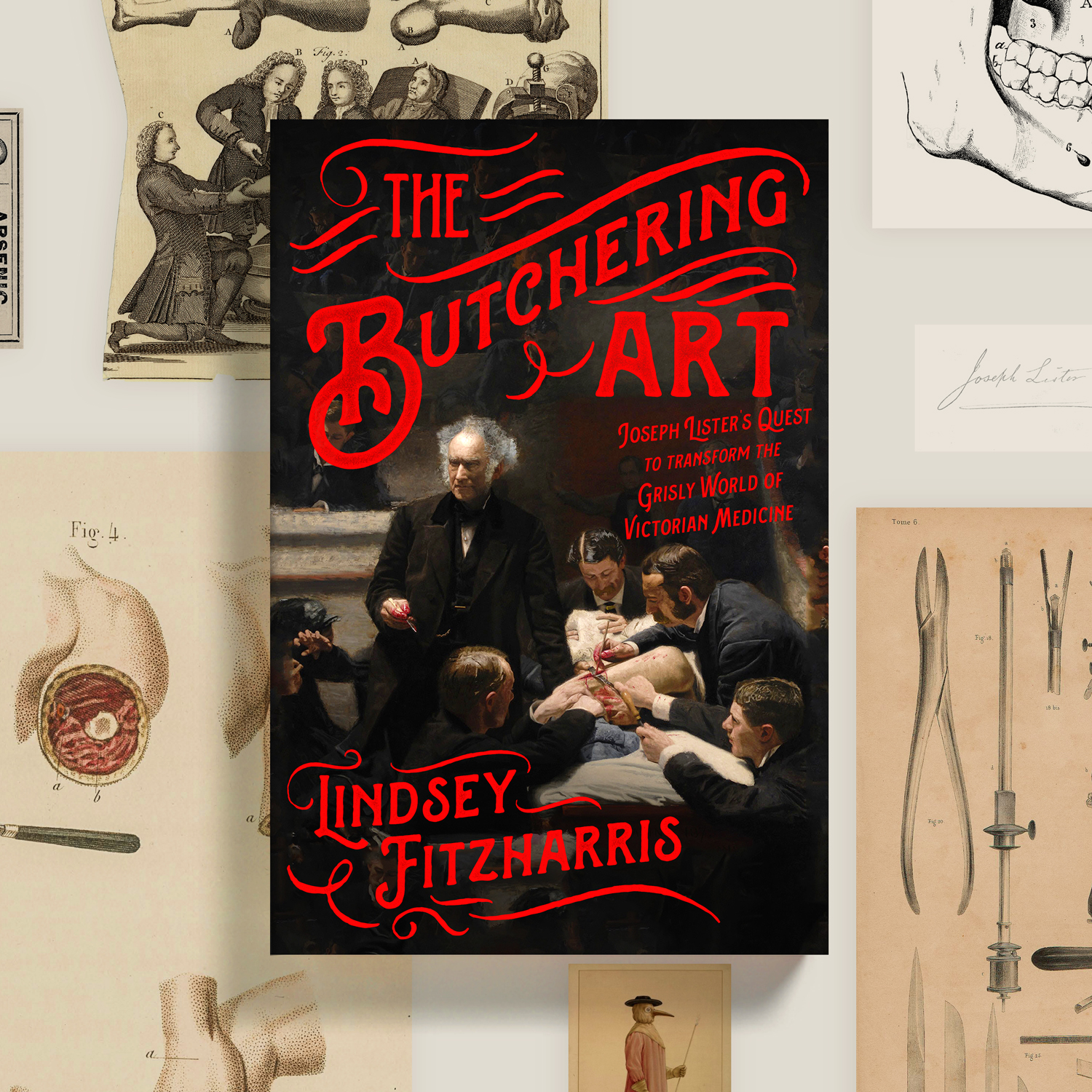

The following blog post relates to my forthcoming book THE BUTCHERING ART, which you can pre-order here.

The following blog post relates to my forthcoming book THE BUTCHERING ART, which you can pre-order here.

Today, we think of the hospital as an exemplar of sanitation. However, during the first half of the nineteenth century, hospitals were anything but hygienic. They were breeding grounds for infection and provided only the most primitive facilities for the sick and dying, many of whom were housed on wards with little ventilation or access to clean water. As a result of this squalor, hospitals became known as “Houses of Death.”

The best that can be said about Victorian hospitals is that they were a slight improvement over their Georgian predecessors. That’s hardly a ringing endorsement when one considers that a hospital’s “Chief Bug-Catcher”—whose job it was to rid the mattresses of lice—was paid more than its surgeons in the eighteenth century. In fact, bed bugs were so common that the “Bug Destroyer” Andrew Cooke [see image, left] claimed to have cleared upwards of 20,000 beds of insects during the course of his career.[1]

The best that can be said about Victorian hospitals is that they were a slight improvement over their Georgian predecessors. That’s hardly a ringing endorsement when one considers that a hospital’s “Chief Bug-Catcher”—whose job it was to rid the mattresses of lice—was paid more than its surgeons in the eighteenth century. In fact, bed bugs were so common that the “Bug Destroyer” Andrew Cooke [see image, left] claimed to have cleared upwards of 20,000 beds of insects during the course of his career.[1]

In spite of token efforts to make them cleaner, most hospitals remained overcrowded, grimy, and poorly managed. The assistant surgeon at St. Thomas’s Hospital in London was expected to examine over 200 patients in a single day. The sick often languished in filth for long periods before they received medical attention, because most hospitals were disastrously understaffed. In 1825, visitors to St. George’s Hospital discovered mushrooms and wriggling maggots thriving in the damp, soiled sheets of a patient with a compound fracture. The afflicted man, believing this to be the norm, had not complained about the conditions, nor had any of his fellow convalescents thought the squalor especially noteworthy.[2]

Worst of all was the fact that a sickening odor permeated every hospital ward. The air was thick with the stench of piss, shit, and vomit. The smell was so offensive that the staff sometimes walked around with handkerchiefs pressed to their noses. Doctors didn’t exactly smell like rose beds, either. Berkeley Moynihan—one of the first surgeons in England to use rubber gloves—recalled how he and his colleagues used to throw off their own jackets when entering the operating theater and don ancient frocks that were often stiff with dried blood and pus. They had belonged to retired members of staff and were worn as badges of honor by their proud successors, as were many items of surgical clothing.

The operating theaters within these hospitals were just as dirty as the surgeons working in them. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, it was safer to have surgery at home than it was in a hospital, where mortality rates were three to five times higher than they were in domestic settings. Those who went under the knife did so as a last resort, and so were usually mortally ill. Very few surgical patients recovered without incident. Many either died or fought their way back to only partial health. Those unlucky enough to find themselves hospitalized during this period would frequently fall prey to a host of infections, most of which were fatal in a pre-antibiotic era.

The operating theaters within these hospitals were just as dirty as the surgeons working in them. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, it was safer to have surgery at home than it was in a hospital, where mortality rates were three to five times higher than they were in domestic settings. Those who went under the knife did so as a last resort, and so were usually mortally ill. Very few surgical patients recovered without incident. Many either died or fought their way back to only partial health. Those unlucky enough to find themselves hospitalized during this period would frequently fall prey to a host of infections, most of which were fatal in a pre-antibiotic era.

In addition to the foul smells, fear permeated the atmosphere of the Victorian hospital. The surgeon John Bell wrote that it was easy to imagine the mental anguish of the hospital patient awaiting surgery. He would hear regularly “the cries of those under operation which he is preparing to undergo,” and see his “fellow-sufferer conveyed to that scene of trial,” only to be “carried back in solemnity and silence to his bed.” Lastly, he was subjected to the sound of their dying groans as they suffered the final throes of what was almost certainly their end.[3]

In addition to the foul smells, fear permeated the atmosphere of the Victorian hospital. The surgeon John Bell wrote that it was easy to imagine the mental anguish of the hospital patient awaiting surgery. He would hear regularly “the cries of those under operation which he is preparing to undergo,” and see his “fellow-sufferer conveyed to that scene of trial,” only to be “carried back in solemnity and silence to his bed.” Lastly, he was subjected to the sound of their dying groans as they suffered the final throes of what was almost certainly their end.[3]

As horrible as these hospitals were, it was not easy gaining entry to one. Throughout the nineteenth century, almost all the hospitals in London except the Royal Free controlled inpatient admission through a system of ticketing. One could obtain a ticket from one of the hospital’s “subscribers,” who had paid an annual fee in exchange for the right to recommend patients to the hospital and vote in elections of medical staff. Securing a ticket required tireless soliciting on the part of potential patients, who might spend days waiting and calling on the servants of subscribers and begging their way into the hospital. Some hospitals only admitted patients who brought with them money to cover their almost inevitable burial. Others, like St. Thomas’ in London, charged double if the person in question was deemed “foul” by the admissions officer.[4]

Before germs and antisepsis were fully understood, remedies for hospital squalor were hard to come by. The obstetrician James Y. Simpson suggested an almost-fatalistic approach to the problem. If cross-contamination could not be controlled, he argued, then hospitals should be periodically destroyed and built anew. Another surgeon voiced a similar view. “Once a hospital has become incurably pyemia-stricken, it is impossible to disinfect it by any known hygienic means, as it would to disinfect an old cheese of the maggots which have been generated in it,” he wrote. There was only one solution: the wholesale “demolition of the infected fabric.”[5]

It wasn’t until a young surgeon named Joseph Lister developed the concept of antisepsis in the 1860s that hospitals became places of healing rather than places of death.

It wasn’t until a young surgeon named Joseph Lister developed the concept of antisepsis in the 1860s that hospitals became places of healing rather than places of death.

To read more about 19th-century hospitals and Joseph Lister’s antiseptic revolution, pre-order my book THE BUTCHERING ART by clicking here. Pre-orders are incredibly helpful to new authors . Info on how to order foreign editions coming soon. Your support is greatly appreciated.

1. Adrian Teal, The Gin Lane Gazette (London: Unbound, 2014).

2. F. B. Smith, The People’s Health 1830-1910 (London: Croom Helm, 1979), 262.

3. John Bell, The Principles of Surgery, Vol. III (1808), 293.

4. Elisabeth Bennion, Antique Medical Instruments (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), 13.

5. John Eric Erichsen, On Hospitalism and the Causes of Death after Operations (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1874), 98.